Introduction: Leonardo da Vinci

The world knows Leonardo da Vinci as an artist for his timeless masterpiece, Mona Lisa.

In fact, he was far more than an artist. He was a universal architect who created the blueprint for the AI age.

He was the visionary architect of mechanical intelligence. He is a key link in the journey of discovering “smart machines.”

The Bridge of Genius: From Ancient Epics to the Renaissance

In our previous article, “The History of Artificial Intelligence: From Ancient Myths to Mechanical Reality,” we explored the visionary weaponry of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, where ancient Indian epics first conceptualized “smart” technology. That torch of innovation was carried forward by the 12th-century Arab engineer Al-Jazari, who brought complex mechanics to life.

Now, we arrive in the 15th century to meet the ultimate peak of this lineage: Leonardo da Vinci.

In this article, we will dive into the “Super Genius” of Leonardo. We will explore why his brilliance remained hidden for centuries and why his monumental work was tragically excluded from the formal Scientific Revolution.

Finally, we will see why modern progress is impossible without acknowledging the foundations he laid.

The Man and His World

Leonardo’s life was a journey of dramatic peaks and valleys, where his achievements were deeply shaped by the turbulent times he lived in. To truly understand his genius, we must look at the world that forced him to constantly adapt, moving him from the role of a peerless artist to that of a military and civil engineer.

His frequent migrations, often driven by war and shifting power, were not just a struggle for survival; they were the catalysts that expanded his mind into every field of human knowledge.

A Brief Life Sketch

Leonardo (1452–1519): A Brief Life Sketch

1452 (The Outsider): Born in Vinci as an “illegitimate” son.

He could not get a formal education, so he turned to Nature as his primary teacher.

1466 (The Apprentice): In Verrocchio’s workshop, he mastered everything from metallurgy to mechanics, merging art with engineering.

1482 (The Military Engineer): Moved to Milan and pitched himself to the Duke not as a painter, but as a war engineer—the era where his robotic concepts were born.

1503 (The Masterpieces): Began the painting Mona Lisa, and conducted deep anatomical research, carrying his notebooks everywhere to record the “language of nature.”

1519 (The Legacy): Passed away in France, leaving behind thousands of pages of journals that remained hidden from the world for centuries.

Specific Moments: The Turning Points

Leonardo’s life was a journey of dramatic peaks and valleys, but two specific moments defined the legend we know today. These turning points transformed him from a talented apprentice into the ultimate visionary.

Let’s explore these two defining time periods:

The Mysterious Gap: The Birth of a ‘Super Genius’ (1476–1478)

Between 1476 and 1478, Leonardo virtually disappeared from public record.

This mysterious disappearance is considered the most important event in Leonardo’s life.

This “gap” followed a devastating and painful public accusation of sodomy, a serious crime in 15th-century Florence that could have cost him his life. Shaken and humiliated, the young artist retreated into a period of mysterious obscurity.

The Cave and the Transformation:

Legend suggests Leonardo spent this isolation exploring a deep, dark cavern. He wrote of feeling torn between the “fear of the threatening darkness” and a “burning desire” to uncover its secrets. When he re-emerged in 1478, his intellectual capacity had undergone a massive leap. He returned with an uncanny understanding of human anatomy, planetary motion, and futuristic machines that seemed impossible for his era.

Transformation of Leonardo: Alien Theory vs. Natural Genius

For Leonardo’s sudden evolution. Some alternative theorists, including proponents of the “ancient alien” hypothesis, offer a provocative explanation. They suggest that during his two-year disappearance, Leonardo may have encountered aliens, resulting in a profound cognitive “upgrade” that transformed him into a superior genius.

However, biographer Walter Isaacson rejects these supernatural claims, offering a far more grounded and convincing argument. He believes this period was a time of intense, “deep observation.” Instead of meeting beings from another world, Leonardo used his solitude to sharpen his senses and transform nature itself into his greatest teacher.

To attribute his “Super Genius” to the influence of aliens would be a grave injustice to the power of human intelligence; Leonardo’s brilliance was not a gift from supernatural powers, but the result of a mind that learned to see the depth in what others merely looked at.

The Milan Years (1482–1499): The Rise of the Scientist

Leonardo’s tenure in Milan was the defining era where he transitioned from a talented artist to a visionary engineer.

Military Engineering:

The Milan Years: The Rise of the Military Engineer

In 1482, Leonardo moved to Milan, a city ruled by the ambitious Ludovico Sforza. Knowing the Duke was fond of wars, Leonardo pitched himself primarily as a military engineer rather than an artist to secure patronage for his survival.

In a famous letter of application, he showcased revolutionary designs for armored tanks, giant crossbows, and portable bridges. While he mentioned his painting skills only as a footnote.

Achievements in Milan: Engineering the Future

In Milan, Leonardo wasn’t just an artist; he was a high-level engineer. He treated the city and the battlefield as his personal laboratories.

The Mechanical Knight: Leonardo designed the world’s first humanoid robot. Using gears and pulleys, this “knight” could sit, stand, and move its arms.

Military Innovations: He designed terrifying war machines, including an armored tank, giant crossbows, and even a “triple-tier” machine gun.

Civil Engineering: He planned an “Ideal City” with underground canals and two-level roads to separate pedestrians from carts—a concept used in modern urban planning.

Hydraulic Mastery: He designed advanced lock systems for Milan’s canals, some of which are still in use today.

Leonardo didn’t just dream of the future; he drew the blueprints for it. His work in Milan proved that a single mind could master the mechanics of both war and peace.

The Observer: Decoding the Language of Nature

Leonardo did not receive a formal classical education, but this “limitation” became his greatest strength. He proudly called himself a “disciple of experience,”

He treated Nature as his only true teacher and the ultimate laboratory. He proved that true knowledge is found in observation, not heavy textbooks.

The Science of Flight: By studying bird wings, he drafted blueprints for the Ornithopter and the Aerial Screw (the helicopter’s ancestor).

His triangular Parachute design was proven to work perfectly in a modern test in 2000.

The Geometry of Nature: Leonardo’s Rule of Trees

Through his deep observation of nature, Leonardo discovered that trees follow a strict mathematical code. He realized that a tree is not just a random shape, but a masterpiece of biological engineering.

Leonardo’s “Rule of Trees” explains the precise relationship between a trunk and its branches:

Equal Thickness: At any height, the total thickness of all branches is equal to the thickness of the main trunk.

Branching Balance: When a branch splits, the combined thickness of the new sub-branches equals the thickness of the original branch.

Sap & Strength: This design allows the tree to distribute sap efficiently and resist the force of the wind.

This wasn’t just an artist’s sketch—it was a scientific discovery. Today, this exact principle is used in Computer Graphics (CGI) to create the realistic digital forests we see in movies and video games.

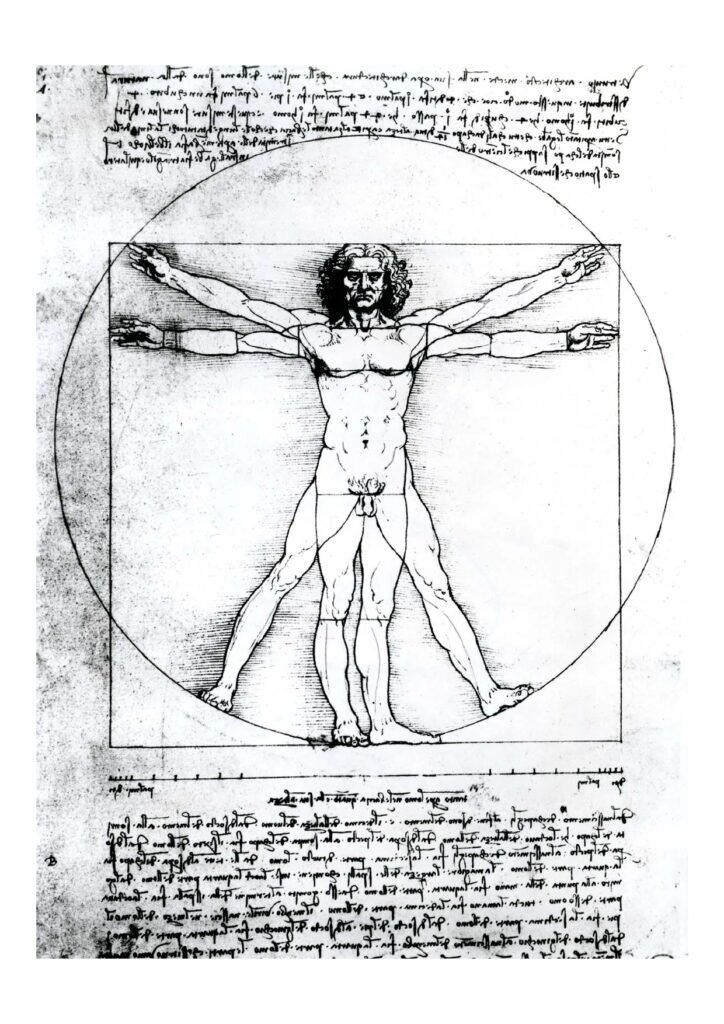

The Geometry of Life: The Vitruvian Man

Vitruvius, a Roman engineer and architect whose work was rooted in deep philosophy, believed that the human body is a “microcosm” of the universe. He argued that perfectly balanced human proportions connect the physical earth (the square) to the divine heavens (the circle). Essentially, the human form is the ultimate mathematical blueprint for all creation.

Inspired by this, Leonardo created the world-famous Vitruvian Man (1490).

This was more than a sketch; it was a profound philosophical and mathematical coordination of the human body.

Leonardo observed that the human figure fits perfectly into both a Square and a Circle, establishing a bridge between mathematics and philosophy:

- The Square: Represents the earthly, physical world.

- The Circle: Represents the spiritual, cosmic realm.

By showing man at the center of both, Leonardo demonstrated that “Man is the measure of all things.”

He identified proportions so accurate that they are still used in forensic science today:

- The Reach: Arm span equals total height.

- The Face: The chin-to-forehead line is 1/8 of the body height.

- The Foot: Foot length is approximately 1/6 of the total height.

Through this “Universal Blueprint,” Leonardo proved that the human body is a masterpiece of geometric engineering.

The Golden Ratio – Phi ()

In collaboration with Luca Pacioli (the father of modern accounting), Leonardo conducted a deep study of the Golden Ratio (1.618).

They discovered that anything perceived as “beautiful” or “balanced” in nature follows this specific ratio.

In their book ‘De Divina Proportione’ (Divine Proportion), they argued that this isn’t a coincidence but a “Divine Signature.”

Hydrodynamics: He mapped the “turbulence” of water currents centuries before the term existed, applying these insights to visionary canal systems and dam designs.

Decoding the Secrets Beneath the Skin (Anatomy)

For Leonardo, understanding the human body was the ultimate engineering challenge. At a time when the Church forbade human dissection, Leonardo risked everything, clandestinely dissecting over 30 cadavers by candlelight to uncover the “truth beneath the skin.”

Overturning Myths: Leonardo proved that 1,300-year-old medical theories (by Galen) were wrong because they were based on animal, not human, anatomy.

The Heart as a Machine: He was the first to describe how heart valves function and how blood creates “vortices” (swirls) within the chambers—a discovery that medical science didn’t fully confirm until the 1960s.

The MRI of the 1500s: His sketches were so forensic in accuracy that they are often compared to modern CT scans. He mapped the nervous system and spinal cord with three-dimensional precision.

🪞 The Mirror Genius

Leonardo wrote most of his personal notes in Mirror Writing—from right to left. To read his secrets, you have to hold his journals up to a mirror! While some think he did this to hide his ideas from the Church, others believe that as a left-handed genius, it was simply his way of keeping his ink from smudging.

The Fusion of Vision: Optics and the Science of Light

Leonardo did not see Art and Science as separate; for him, a painting was a scientific experiment. He used his mastery of Optics (the study of light) to create masterpieces that feel alive.

Sfumato: The Science of Shadows

Leonardo realized a simple truth of nature: there are no sharp borders in the real world. To capture this, he pioneered Sfumato (meaning “smoky”), a technique that uses soft, blurred transitions between colors and tones instead of hard lines.

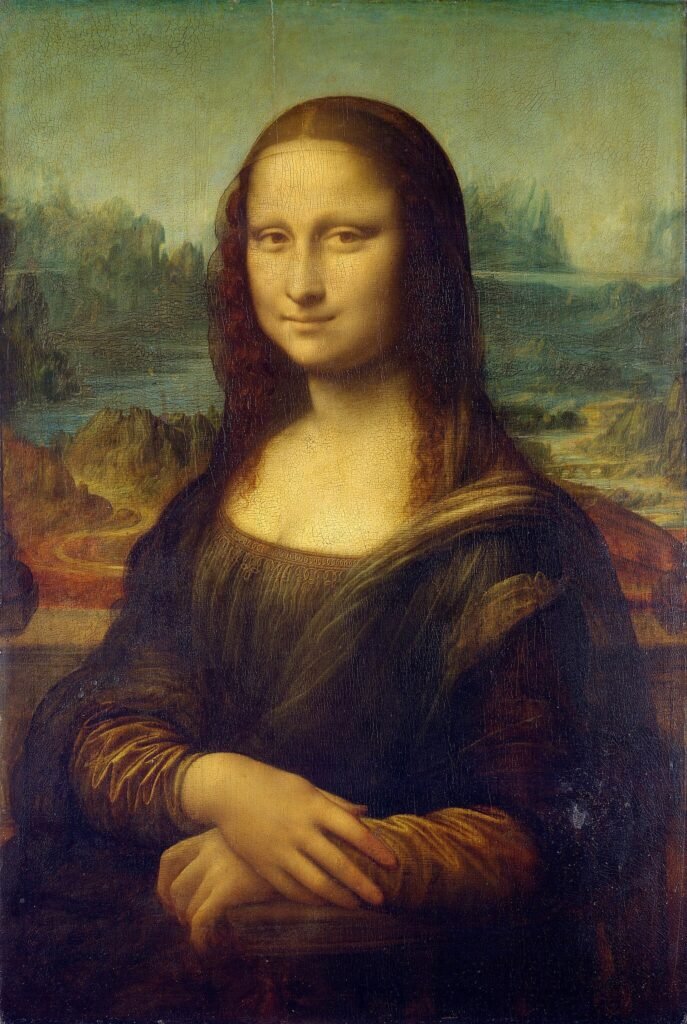

This was a scientific conclusion, not just an artistic choice. He used this technique to create the Mona Lisa, applying thin, smoky layers to the corners of her eyes and mouth. This is why her expression seems to change, and her smile feels “alive”—because there are no hard edges for the eye to lock onto, she appears to breathe within the painting.

Linear Perspective:

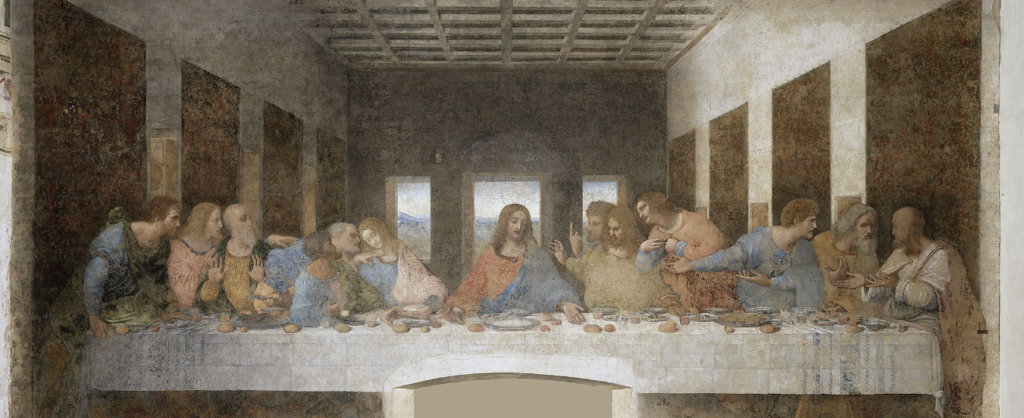

In The Last Supper, he used mathematical precision to create an optical illusion. He proved that science is what makes art feel real, while art allows science to be imagined.

The Anatomy of the Eye: Leonardo was obsessed with how the eye captures images. He studied the lens and retina to understand “perspective,” treating the eye as the primary “machine” of human intelligence.

Art as Visual Science: Leonardo’s Iconic Masterpieces

Behind each of Leonardo’s paintings lies a long story of relentless hard work, imagination, art, and science.

Many of his works are the result of years of research and personal struggle—such as the Mona Lisa, which he carried with him throughout his life, constantly refining it, or The Virgin of the Rocks, where the existence of two versions hides a history of legal disputes and his own obsession with perfection.

Since it is impossible to capture the full depth of these stories here, we offer a brief overview of his world-famous masterpieces. These paintings are not mere art; they are the visual results of Leonardo’s experiments to decode the laws of nature:

The Mona Lisa: The world’s most famous portrait, serving as a profound study of human psychology and the “living” atmosphere.

The Last Supper: A revolutionary achievement in perspective and capturing the “movement of the soul” through facial expressions.

The Virgin of the Rocks: A Tale of Two Versions

Leonardo painted two versions of this work, revealing his evolving mastery of Sfumato (smoky blending) and his scientific precision in geology.

However, the existence of two paintings was sparked by a religious dispute rather than just artistic choice.

The First Version (The “Scientific” Original): This version lacked traditional religious symbols like halos or John the Baptist’s cross. Leonardo wanted to portray the figures as natural, earthly beings within a scientifically accurate cavern.

The Conflict: The Church clients were dissatisfied with the lack of holy markers and the “dark” atmosphere. After a legal and financial dispute that lasted years, a second version was created to meet the Church’s requirements.

The Second Version (The “Traditional” Update): This version added the requested halos and the wooden cross for John the Baptist, making the religious identity of the figures unmistakable.

Where to find them today:

| Version | Location | Museum |

|---|---|---|

| Original (No Halos) | Paris, France | The Louvre |

| Second Version (With Halos) | London, UK | The National Gallery |

Why this matters:

This story proves that even a “Super Genius” like Leonardo had to navigate the “rotten thinking” and rigid demands of the 15th-century Church, showing the constant tension between his scientific realism and the dogma of his time.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne:

A masterpiece of “Sacred Geometry,” exploring how multiple figures interact within a complex three-dimensional space.

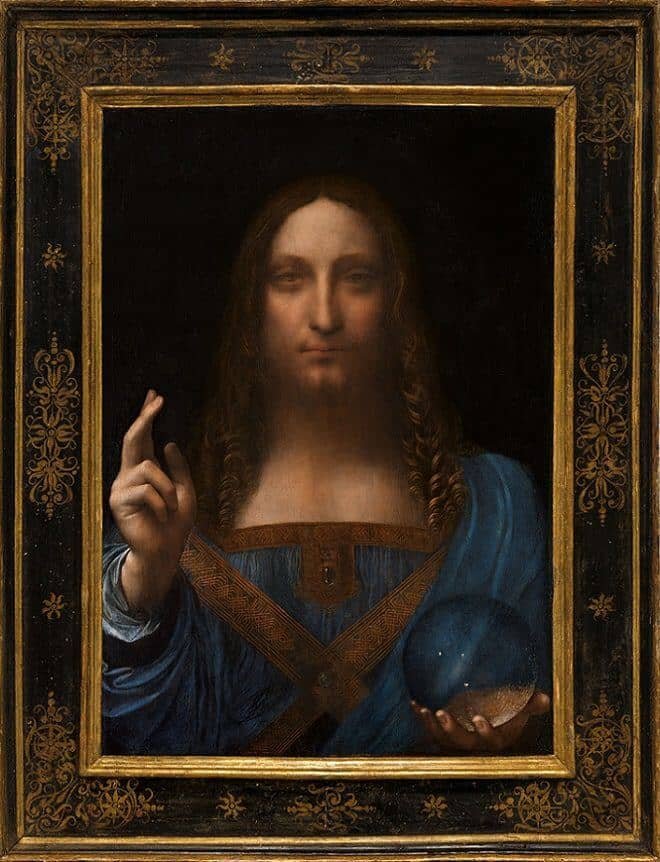

The Salvator Mundi:

A fascinating exploration of optics, demonstrating how light refracts through a crystal sphere.

Lady with an Ermine:

A perfect example of his anatomical precision and his unique ability to capture the “vibration” and life of a living being.

Was Leonardo a nature lover or a designer of deadly weapons?

Leonardo was a man of profound contradictions. He was a vegetarian who cherished all life, yet he served as a military engineer designing terrifying weapons. However, these were not two different personalities, but one.

Leonardo believed that power ensures peace. He felt that a state possessing deadly weapons would discourage enemies from attacking, thereby preventing war.

Yet, the humanist within him feared the destruction his inventions could cause. To protect humanity, he often deliberately left his weapon designs incomplete or included “intentional errors.” This ensured that while the concept existed, no one could actually manufacture them to kill innocent people.

The Ethical Engineer: Sabotaged and Hidden Designs

Leonardo’s journals contain terrifying inventions that he purposefully sabotaged or kept secret to prevent human cruelty. He used “intellectual locks” to ensure his most dangerous ideas died with him:

The Sabotaged Tank:

Leonardo designed a circular armored vehicle with cannons, but he intentionally placed the gears in reverse. If built exactly as he drew it, the wheels would lock, rendering the weapon useless.

The Hidden Submarine:

He conceptualized a diving suit and a submarine for underwater warfare. However, he refused to publish the details, fearing that the “evil nature of men” would use them to sink ships and commit murders on the sea floor.

The “Scythed” Chariot:

While he sketched horse-drawn wagons with rotating blades, he described them as “too monstrous” for actual use, often omitting the final mechanical links required to make them functional.

By leaving these “deadly codes” incomplete, Leonardo acted as the world’s first ethical engineer—choosing to protect life over providing the tools for its destruction.

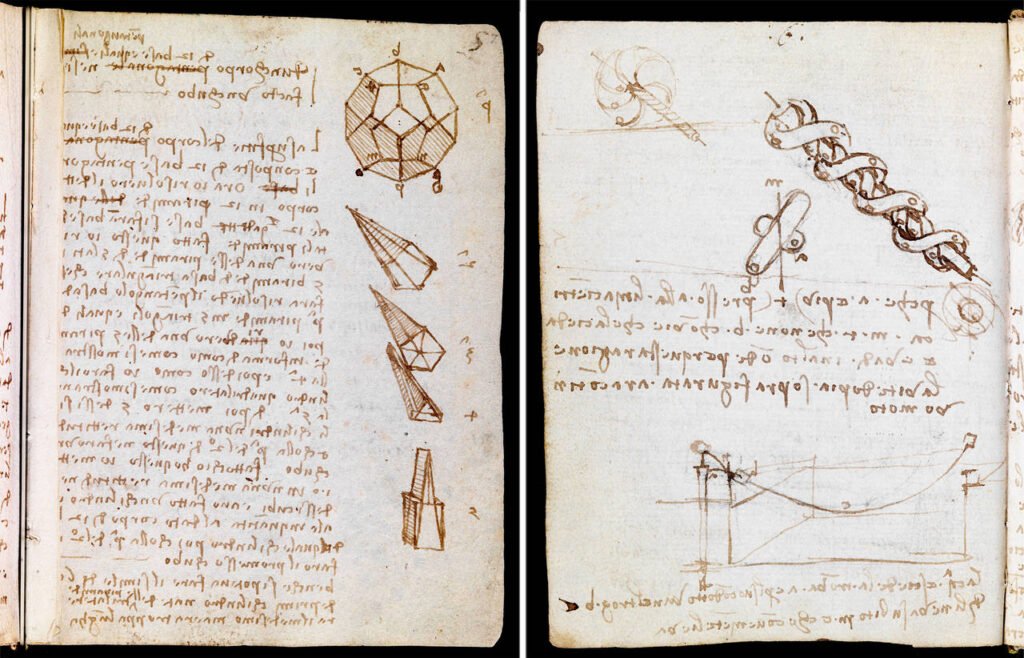

Blueprint of the Future Robotics Science

Centuries before the word “robot” was even coined, Leonardo was already building them.

The Mechanical Knight (1495):

This was a programmable machine that could sit, stand, and move its arms using a complex system of gears and pulleys. It was, in every sense, the 15th-century ancestor of modern robotics.

The Robotic Lion:

Leonardo also built a mechanical lion that could walk across a room and open its chest to reveal flowers. This was a sophisticated example of “Automata”—a machine that combined entertainment with advanced kinetic engineering.

From the Renaissance to Mars: Leonardo’s NASA Legacy

Leonardo’s 500-year-old designs are so advanced that they are still used in space today. In the late 20th century, robotics expert Mark Rosheim used Leonardo’s sketches to successfully build a working model of the “Mechanical Knight.” He found the joint mechanics so efficient and human-like that he used Leonardo’s “code” to develop robots for NASA’s

planetary exploration.

Master of Mechanics:

These inventions prove that Leonardo wasn’t just building toys for kings; he was designing the foundational blueprint for the future of robotic science.

💡 A Legacy Worth Millions

In 1994, Bill Gates recognized Leonardo’s timeless genius by purchasing the Codex Leicester for $30.8 million. To this day, it remains one of the most expensive books ever sold—proving that Leonardo’s 500-year-old insights are still the gold standard for the world’s leading tech visionaries.

The Silent Revolution: Why Leonardo’s Genius was Hidden for 300 Years?

Leonardo was a scientific visionary living centuries ahead of his time. Tragically, his genius did not become part of the formal Scientific Revolution. While later scientists took credit for “discovering” the laws of nature, Leonardo had already decoded them decades earlier.

Historians suggest several reasons why his work remained a “Silent Revolution”:

i. Unpublished Legacy: Although the Gutenberg printing press existed, Leonardo never published his thousands of pages of research. His visionary ideas remained imprisoned within his private journals, known as Codices.

ii. Mirror Writing: Leonardo wrote in ‘Mirror Script’ (reverse handwriting from right to left). While it could be read using a mirror, it created a massive barrier for others, making his thoughts feel like a secret code.

iii. Lack of Systematic Order: His notes were a “stream of consciousness.” On a single page, one might find complex physics formulas and anatomical sketches scribbled alongside mundane kitchen expenses.

iv. Observation vs. Systematization: Scholar Sherwin B. Nuland argues that while Leonardo was a magnificent observer, he lacked the patience to organize his data into formal “Scientific Laws.” He was often lured away by his next great curiosity.

v. The “Artisan” Label: Because Leonardo lacked a formal classical education, the academic world of his time dismissed him as a mere “unlettered” artisan rather than a true scientist.

vi. Fear of the Church: In an era where challenging Church dogma was a death sentence, Leonardo’s work—especially his dissection of over 30 human corpses—was dangerous. Mirror writing may have been his way of protecting himself from charges of heresy.

The Cost of Silence: A Lost Future

Because his findings remained hidden, the Scientific Revolution of the 1600s had to “re-invent” everything Leonardo already knew.

Professor Martin Kemp calls this the “greatest lost opportunity” in human history. He argues that if Leonardo’s research in anatomy and mechanics had been published, humanity would have reached the scientific milestones of the 19th century 200 to 300 years earlier.

🎨 The Apple Connection: Tech Meets Art

Steve Jobs ने Apple की नींव “Technology और Liberal Arts के संगम” पर रखी थी। वे लियोनार्दो को अपना आदर्श मानते थे। Jobs का मानना था कि सच्ची इनोवेशन तब होती है जब वैज्ञानिक दिमाग और कलाकार की आत्मा एक साथ मिल जाते हैं—ठीक वैसे ही जैसे लियोनार्दो ने 500 साल पहले किया था।

The Interdisciplinary Legacy: Science Meets Soul

Leonardo’s true legacy is not a single invention, but a “Systems Approach”—the idea that to understand the part, you must understand the whole. This philosophy serves as the foundation for modern Bio-mimicry and Artificial Intelligence.

The Father of Bio-mimicry: Long before modern drones, Leonardo recognized that nature is the most efficient engineer. His bird-flight studies remain the blueprint for aerodynamic design.

The First “Digital” Thinker: His “Mechanical Knight” used algorithmic logic to execute motion, conceptualizing “software” centuries before the computer.

The Apple Philosophy: This intersection of technology and liberal arts so deeply inspired Steve Jobs that he made it the core philosophy of Apple.

Leonardo proved that progress requires both Data (Science) and Empathy (Art). Today, as we develop AI, we are not just surpassing him—we are finally realizing his vision. He was the first to imagine the “smart machines” that define our lives, leaving a blueprint for a future we are only just beginning to build.

What Leonardo Teaches the Modern Generation

Leonardo da Vinci was a man who lived 500 years ahead of his time. He left a “blueprint” for the future world that we are just beginning to build.

In an era dominated by Algorithms and Robotics, he remains the ultimate guide for the modern generation.

Skills Over Degrees: Talent Beyond Formality

Leonardo was an “outsider” with no formal university education. Yet, he became the most knowledgeable person in history.

Today, visionaries like Elon Musk echo this sentiment, famously stating that “evidence of exceptional ability” matters more than any diploma. Leonardo is the ultimate proof that insatiable curiosity is the true engine of innovation—not just a piece of paper.

Experience Over Information:

Leonardo called himself a “man without letters,” valuing hands-on observation over stale theory. In the age of AI, data is cheap, but deep insight gained through experience remains our most valuable asset.

The Power of Polymathy:

The future belongs to those who bridge technology and the human soul. Science provides the power to build, but human sensibility provides the wisdom to know what is worth building.

Relentless Curiosity:

Leonardo’s “superpower” was an endless need to know “why.” This curiosity is the engine of civilization; it births the technology of every era.

Conclusion: A Debt to Genius

Leonardo da Vinci was a “mobile laboratory” of human potential, a polymath whose versatile mind decoded the universe for his own joy. The tragedy of his hidden work was not his loss, but ours.

Forced into silence by the “rotten thinking” and rigid dogmas of the 15th-century Church, Leonardo whispered his revolution to private journals.

As we enter the AI era, we are finally catching up to his 500-year-old “code.” The lesson is clear – humanity pays the price when genius is silenced.

To honor Leonardo, we must embrace his spirit: where science seeks the truth and art finds the soul, creating a future built on curiosity and compassion.